Personal Style Is Dead And The Algorithm Killed It

We are no longer adopting trends popularized on social media, we're letting apps themselves create them.

The concept of the “stock character” dates all the way back to Ancient Greek theatre, the time of Aristophanes and Aeschylus, when actors would don large masks with static expressions and (in comedic theatre) large prosthetic phalluses. The presence of the stock character, much like the mask, was simple: to immediately alert an audience to a character’s nature and motivations. Many of these plays did not dwell on the individuals depicted, forsaking character growth for plot movement. Some stock characters have stuck around (tropes of the lover, the mother, the fool, the hero seem as old as storytelling itself), while others (the beatnik, the flapper) are ephemeral depictions of bygone cultures.

Much like stock characters, cultural movements are named in part to reduce them to similarly-digestible levels of flatness. Bohemians, hippies, punks, hipsters, dandies…these terms all try to encompass vast movements into a handful of monolithic and universal parts. Few counterculture movements name themselves, usually labelled instead by those seeking to come up with a categorization, a label, or a definition so that they have something concrete to oppose. Of course, these movements will eventually become almost entirely commercial, enveloped into whatever “mainstream” culture is as soon as there is profit to be made.

But what if “alternative culture” didn’t end with commercialisation, and instead began with it?

We live in the world of the “niche aesthetic”, a series of identity and style groupings usually with two-word names like Coastal Grandma, Coconut Girl, and Bimbo-Core. The progenitor of the contemporary niche aesthetic is most likely the Art Hoe movement, an internet subculture that began as a celebration by and for BIPoC artists and ended with white girls buying mustard-yellow kanken backpacks and wearing Van Gogh socks. Since then, these assorted style movements have been born, had their brief heyday, and quickly and quietly died, like Zara-clad mayflies. Most of the named movements that thrive on social media are target towards young women, but similar style trends reach young men’s fashion as well; picture the Thrasher T-Shirt / Camo Cargo Pants moment of 2016 or the Dickies Pants / Carhartt Beanie / Teal American Spirits culture that would follow. These movements largely begin with clothes and accessories but branch out into a sort of lifestyle philosophy, like the granola girl that works to save the bees or the stone-cold Lana Del Rey listener that never cries over boys (except when she does). They are, to put it plainly, stock characters.

There is plenty of well-researched, thoughtful writing critiquing fast-moving microtrends, observing the environmental and labor impact of these hyperconsumerist cultures. I agree with most of them. Any time these points are brought up, scores of internet commenters armed with their parents’ Amazon Prime accounts lash out cries of misogyny, unified by a rallying cry of “If it’s not hurting anyone, what’s the problem?” (The rebuff is simple: these things do hurt people, mainly people in the Global South, who tend to be both the hardest hit by climate change and the hands and bodies behind mass textile production.) But there is also a more subtle, psychological cost in our enthusiastic self-tropification.

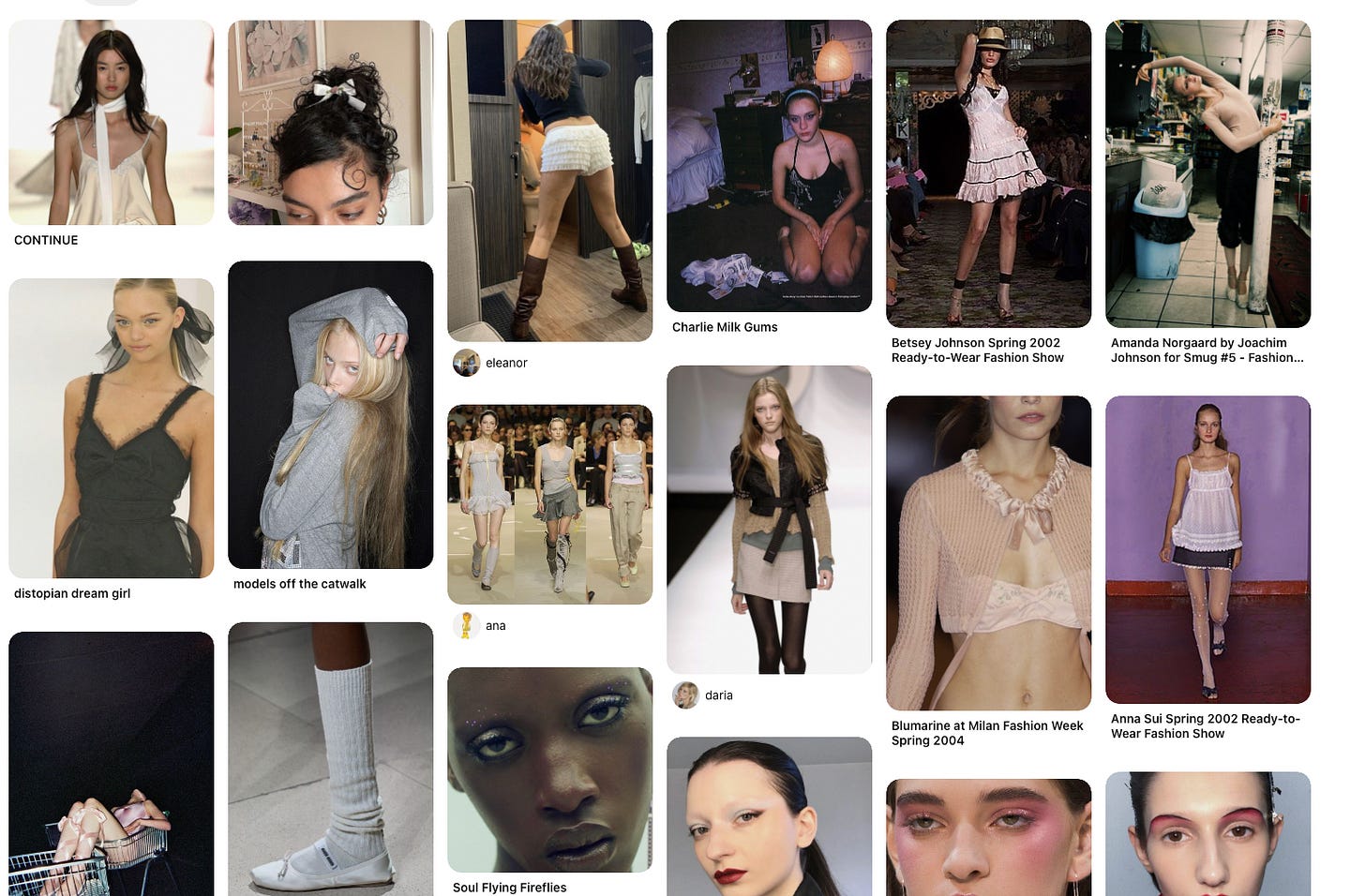

The embrace of niche aesthetics has been framed by some as liberatory: no longer is there a singular mainstream trend; consumers may now select from an ever-growing list of curated styles that come neatly packaged in Pinterest boards with self-mandated diversity quotas and search-term keywords. According to these voices, niche aesthetics allow people to find their personal style.

With any critical thought, the irony is apparent: how can personal style, something unique to an individual, be embodied in two-word phrases shared with swarms of others?

Every person offers immediate social signifiers with their clothing. Sometimes this is obvious: clothing covered in logos with a certain designer’s name, outfits comprised of attention grabbing colors or loud patterns, garments and uniforms associated with particularly career paths. Even the person picking their smelly sweatpants off the floor and hastily pairing them with a wrinkled t-shirt is offering a social signifier, either I do not care what other people think of my clothing or I want people to think that I do not care what people think of my clothing. It would be ridiculous and ahistorical to claim that there was a time in modern fashion where clothing didn’t function as a form of social exchange or that social identity has ever been extricable from consumption.

But our contemporary understanding of identity, by way of these “niche aesthetics”, are not social identities later commodified. They begin with consumption, any sort of cultural or philosophical unification is a latter addition. A single, branded item becomes the basis for a group identity; one does not need to own this item, simple aspire towards what it represents and place themselves in a network of like-minded consumers.

The structures of social media heavily reenforce commodity-based niche aesthetics. Certainly, influencers, celebrities, and socialites have always influenced people into purchasing things or adopting specific trends and styles. What is unique to our contemporary media landscape is the role in which algorithms play in building our consumer identities: Tik Tok’s main feature is its endless, algorithmically generated For You page. Instagram has continually increased its focus on suggested content, both in the Explore page and on its main feed. Specific objects become units of data, like a geotag or hashtag, which can be analysed and promoted based on a user’s previous interaction history. Without any human involvement, a social media algorithm can notice that some users who enjoy content about female-driven coming-of-age movies will be receptive to fashion videos that feature iced coffee in glass mason jars and platform oxford leather shoes. The algorithm then promotes content that synthesizes the most trend-friendly images, ideas, and products. In this way, contemporary social media does not reenforce niche identity groupings but actively creates them, selecting the exact products and commodities that can be grouped together to target and captivate specific markets.

These trends, born from combining products and allowing a social identity to follow, become more and more ridiculous by the day. Take, for example, the “Victoria Paris socks”, which are quite literally white Hanes ankle socks from Target. There was a brief moment in which “Ballerina sleaze” briefly captured the internet—another “aesthetic” that functions more as a search term to bring consumers to heather-grey Brandy Melville tank tops and knock-off Miu Miu ballet flats. Of course, pale pinks and smudged eyeliners are not bad or inherently harmful, but by constantly inventing a new language, the same images and ideas can be resold as new trends or innovative styles rather than recapitulations of the same images, ideas, and aspirations. “Ballerina sleaze” is made up of demure, quiet femininity with a hint of sexuality; what is supposed to be radical or inventive about a woman who keeps her mouth shut, dresses like a child, and yet maintains an adult sexuality?

We see combinations of commodities, label them as trends and movements, assign them philosophies and personalities, and then decide to become the stock characters we didn’t even invent. Worst of all—we believe our tastes and desires are some sort of natural or innate phenomena rather than one that is shaped by a lifetime of socialization and a media culture that carefully selects the things that will allow us to access a feeling of group identity or community. Radical principles of joy are misunderstood; the fetishization of the commodity is mistaken as an expression of self-love and the cohort of consumers within a trend is mistaken for a group bonded in solidarity. Not only does this reduce our capacity to look thoughtfully at aesthetics and trend movements, but it actively deflects cultural criticism as negativity or misogyny (despite the pressure of an in-group, out-group nature fast-moving trend cycle being a force felt mostly by women).

Clothing is political, it is historical, it is communicative. The nuances of fashion should not be reduced to data-driven fodder for algorithms and targeted advertisements. (Why on earth is there (more than one) Shein Keffiyeh (1, 2)?) Our consumer fashion culture is pure simulacra, trends based off ideas based off histories that are totally imagined, either by machines or marketing experts. And it should go without saying, but there are, of course, many individuals with great, organic personal style (Myra Magdalen, Kadijah, Albert Muzquiz, my friend Ryann), inspired by historical fashion movements, film and art they like, and attention to detail. How much more interesting it is to think about clothing as a vehicle with which we examine the present, the past, and the future than dressing like an extra in a film about the general admission pit at a Harry Styles concert.

Perhaps this all seems overblown, unimportant, a too-close read into something as silly as popular fashion. But it is exactly because fashion trends are taken as mundane that they become so important: we are always wearing clothing; it is the one commodity we cannot leave the house without. It is laden with philosophies and histories that conjure subconscious associations in our head, dictating our ability to analyse ourselves and others without ever seeming particularly important or existential. Our consumption of clothing and discourses around fashion reveal how we think about commodities, labor, social groupings, our own self worth, and our relationship to power. The global textile industry—an industry obviously rife with human trafficking, slavery, and ecological destruction—is valued at over one trillion (with a T) dollars for the year 2022. The people that control garment production have immense economic and therefore political power; if the discourses surrounding consumption are of concern to them then they must also be of concern to us.

Of course, it is human nature to want to be seen in a particular way, to identify ourselves as part of a group or culture or movement. We want to signal our values to our communities—it leads us to safety, companionship, love. But the solution is not blind acceptance of algorithmically generated shopping lists, polyester paradises to be changed with the seasons.

Lately, I found myself reminiscing about everything I used to like at the age of 13 (2012), and I noticed that all of my interests back then were very niche, very specific and they had lasted for so long and still accompany me to this day. The thing that's been on my noggins the past couple of weeks is how today's generation can't even honestly have that luxury, TikTok, Pinterest, and Instagram feed them these ready-to-wear personas. Instead of slowly discovering and LOOKING for what they like with their own will, the algorithm shoves down their throats hashtags and micro trends.. Clean Girl this, Villain era that, femcel this, heroin chic that... I think they really aren't allowed to truly find themselves unless they take a break from social media?

this was really well written. i find it astonishing how fast and rapid these trends have now become. some micro trends last for 2 weeks before being discarded for the next best thing. when everything is now designed to be rapidly consumed, is there room for lasting self expression?