The Ontology of Womanhood

and we miss when we talk about reproductive health

It finally happened: today, I was disparagingly called a liberal by a random online. Why was I called a liberal? What could I have done to inspire such ire, to be the subject of such vitriolic verbiage that I was slapped with the label most disparaging to anyone on the left? I said that I think that it is important to not equate women with pregnancy and that we cannot disregard gender-inclusive language for the sake of convenience or brevity.

I think there is merit in critiquing purely aesthetic forms of language that function only as social signifiers for the well-to-do, hyper-online, professional-managerial class. But to write off all linguistic discourses as inherently empty shows a fundamental misunderstanding of how language operates and the very real implications that language has on our lives. How do we mediate the space between liberal identity politics and a grounded, materialist function of language? First, we need to address the function of language. Contemporary language does not exist just to create verbal representations of material things. The bulk of language-based communication isn’t grounded in some sort of physical relationship between words and their meanings, but rather in connotation: why we choose the words we do. Our choice of language can reveal our geographic origin, our socioeconomic class, where we went to school, the way we see ourselves. The phrase “Excuse me, but I think the cafetière might not be working…” is vastly different than the phrase “Coffee machine’s broken.”

There is a type of corporate bourgeois liberalism born out of HR meetings and Robin D’Angelo speaking fees that stresses that some words are bad because they are distasteful. This abstract view of language is meaningless— if someone were to say “We need to increase social services for the homeless,” and the response is to use the phrase “actually, you’re supposed to say unhoused,” the conversation has moved away from the material analysis and towards the egos of the individuals based on their familiarity with politically correct language. Even when well-intentioned, the desire to participate in the correct image of activism often not only ignores the material issues people face but intentionally obfuscates them.

But we cannot ignore that the power to define language has long been a tool of control by oppressing systems. The power of language definition is part of a larger aspect of social control, the innate desire for oppressors to categorise, other, and subjugate the people they oppress. The issue of using the phrase “Indian” versus “Indigenous” to refer to the original occupants of the Americas is a materialist issue—one term is the label chosen by colonisers to impose on others, the other is a term that specifically denotes a historical relationship with colonialism and the violence inherent to it. The same goes for slurs; the harm in a slur is not the fact that it is an off-limits word that is impolite, but that it recalls direct material histories of violence. The words we use shape the way we move through the physical world; consider the British imperial practice of Anglicising the names of places, something that actively weakens indigenous connection to their land and operates as a tool of both cultural and physical genocide.

Why, then, is it so hard to apply this understanding to the way we talk about gender? And why do we continue fail to apply this thinking to reproductive health?

In many circles, there is an understanding that “not all women have vaginas, not all people with vaginas are women”. Personally, I don’t know anyone that would publicly argue otherwise, though that fact is entirely due to my upbringing in liberal, New England, urban bubbles. The idea that this type of gender inclusivity is so pervasive in so many spaces is radical and felt almost unimaginable, even five years ago. But even for people that can espouse the basic rhetoric of trans acceptance, something still is missing.

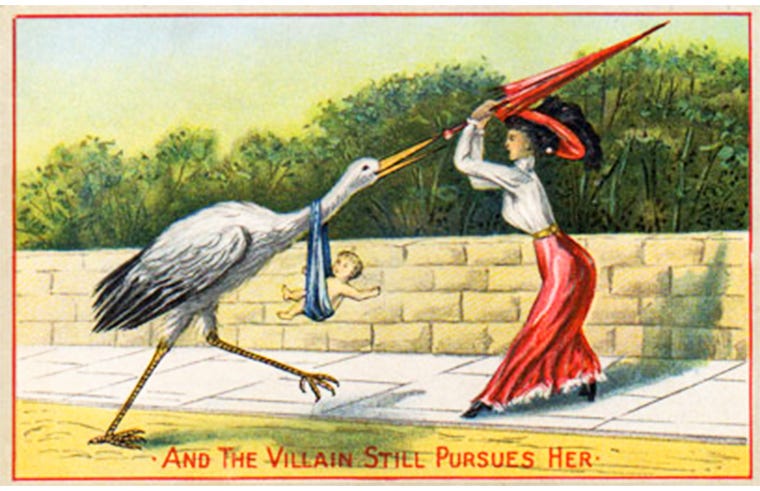

In discussing reproductive healthcare, there is this subtextual idea that abortion is a fundamentally women’s issue with the acknowledgement that there are other people who can get pregnant. And certainly, women are the largest group of people that get abortions. You’d be hard-pressed to find anyone who would argue with that. But to understand pregnancy as a woman’s issue is to do a disservice to everyone involved—including cis women.

We tend to over-complicate our inclusive language, rather than think simply and clearly about what we mean to say. When talking about abortion, we’ve moved from “women” to “women and trans men” to “women and non-binary and trans people” to “people with vaginas” to “people with uteruses”. While abortion and pregnancy affect everyone, including people who will never be pregnant, we’ve ignored the most obvious of phrasing to discuss people who get abortions. Abortions are had by people who get pregnant.

But what is the harm in every-so-often slipping up, in using the phrase “women” as a stand-in for “people who get pregnant”, especially when women make up the bulk of people who get pregnant? Surely, this could be construed as yet another form of liberal language policing, unproductive in its implication beyond a sense of grandiose fulfilment.

Except… not at all. In practice, quite the opposite. The way we talk about women, the way we define women by the usage of words like “women’s health” and “womanhood”, in turn shapes the way we see and treat women—and everybody else. Not conflating women with pregnancy isn’t solely an issue of inclusivity or visibility, it is an issue of understanding power and addressing institutionalised misogyny.

I will not be the first person to point out that not all cis women can get pregnant. Some are born that way with genetic conditions, some lose their ability to become pregnant through illness or accident, many cis women reach the age at which they undergo menopause. No one in their right mind would jump to say that these people are any less of a woman than someone who could get pregnant. Likewise, there are trans men and non-binary people that can get pregnant, give birth, breastfeed. As such, there is no practical or biological tie between women and pregnancy. Of course, we have cultural ties, expectations of motherhood, ideas of what it means to be maternal. Women who lose the ability to become pregnant often mourn this loss not only as a bodily function but as a cultural role imposed by seeing birth as necessary to complete their own identity.

But when we conflate women with pregnancy we reveal the way we see women, trans people, and even men. To conflate womanhood with pregnancy is to say that there is a biological and ontological relationship between women and motherhood, that women are predisposed to be mothers, and that womanhood is (and will always be tied to) pregnancy and giving birth..

This is the exact argument given by systemic patriarchy, it is the same bioessentialism that has held all women back as long as patriarchy has existed. If we are to say that pregnancy is the unifying definition of womanhood, we are saying that the function of womanhood is to be someone who can become pregnant. The idea that pregnancy is intrinsic to womanhood is what has kept women in the home, underpaid, over-exploited, and trapped to see themselves only as the composite of their bodies for centuries. How can a cis woman expect to be liberated if she sees herself only as a singular bodily function? Defining a person by what labor their body can perform for their oppressing group is at the core of almost all historical subjugation.

The relationship between language and the material world is not one-sided, we do not only develop language to describe the world around us. We are also shaped by the way we are labelled, the way we are grouped, the words in which we use to describe ourselves and others. Our psychology is in part shaped by the education given to us by systemic evils and we must do the work of unpacking and unravelling what may seem like innate states of nature. It is not until our own minds fully believe that we are more than our bodies, more than the labels handed down to us by patriarchy, imperialism, colonialism, capitalism that we can make the radical physical, material, and redistributive changes that will benefit us all.

Recommended further reading:

Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writing, Michel Foucault

The Argonauts, Maggie Nelson

this is an excellent and profound analysis thank you so much for sharing this!! i was thinking abt this earlier, the necessity of including trans ppl in the discussion of abortion, and i think another point is that tying together the issues of women and trans ppl makes explicit the correlation between the suppression of gender nonconformity and the oppression of women- it is important to emphasize this link between trans rights and feminism because recent legislation that aims to suppress transitioning and abortion are similar in that they limit marginalized genders’ autonomy, and that underlying issue of subjugation and domination is essential to understanding and analyzing the regressive politics we are seeing. (so sorry if this comment is too long i didn’t realize how much i typed but still thank u for ur insight and ur work!! <3 thankful to have been introduced to ur work through this)

genius article, saying everything I wish I could say & more. definitive ❤️