There Is No "Choice" In Wellness Culture

Over and over again, industries built on pyschosocial manipulation sell us our own insecurities as empowerment choices.

Most people are not stupid. Most people know that the makeup industry, the diet industry, the cosmetic surgery industry were created to prey on our insecurities and sell us a product in return. This is hardly controversial.

Most people are not malicious. Most people know that when we buy these products and use them we have not committed some sort of grand political failing for wanting to be accepted, optimistically hoping that the promise of love and empowerment might just be true this time or cynically accepting that the person that is a size small with clear skin and bright eyes is more likely to receive a job offer or a date or even just a free drink at the bar.

And yet, something remains missing. While we are able to recognize that these industries are fundamentally exploitative and that our attachment to them is a reflection of our insecurities and what advertising tells us are our personal and aesthetic shortcomings, pop-feminist rhetoric bends over backwards to defend them. When the market creates a feeling of failure and then sells us their solution, we believe the fulfillment we feel is empowerment or confidence; we believe it is true. Even more, not only do we aspire towards empowerment but we aspire towards becoming empowered, creating a journey, a narrative, usually one dotted with SponCon and SEO-optimized hashtags. Self-care and wellness culture do not aspire towards anything final or complete but rather a perpetual state of consumption-based “improvement” that both satiates our desire for growth and lines the pockets of major consumer industries.

Take, for example, the cultural shift from makeup to skincare, perhaps best embodied by the rise of Glossier (a brand whose products I regularly use—and enjoy). The marketing message was no longer to have “flawless”, poreless skin hidden behind heavy foundations but instead to use light-coverage products to give an effortless, you-but-enhanced look. The covergirls of the 2000s were the girls you could never be, the covergirls of the Glossier era are the girls you could be—if your skin was a little clearer, your lips a little redder, your lashes a little longer. In CEO Emily Weiss’s 2014 launch announcement, she writes that,

“Foundation is not necessarily a skin-colored fluid. It’s your skin, your expression — that you choose to build on (or not). We’re laying the foundation for a beauty movement: one that celebrates real girls, in real life.”

There is something insidious in the messaging of companies like Glossier, Milk, the Ordinary. Their advertising is largely the same; beautiful people with glowing faces and wide smiles hold tubes of cosmetics that match their medium-length manicure. Each model has one or two traits that would be considered somewhat subversive in a traditional beauty campaign: bleached eyebrows, freckles, a few delicate tattoos of cherries or cowboy hats, an art school haircut, a septum piercing…perhaps the model is a young man or—gasp! feminist win!—forty years old. Sans serif fonts, hand-drawn stars and lightning bolts, nightstands adorned with lip gloss and decorative candles that will never be burned. Their products offer the same promise: become the you that’s just out of reach, and empower yourself while doing it. You see this idealized self, who is beautiful and confident without trying, in the ads and in the mirror, an ephemeral companion who will leave you when the serums run out and only return in a perfectly-packed direct-to-consumer parcel. In this sense, empowerment becomes a stand-in for self-improving, requiring not simply a one-time purchase but a commitment to an identity as a consumer.

One 2022 ad for Glossier simultaneously advertises a shine-minimizing serum to consumers with oily faces and a shine-enhancing serum to those with dry faces.

To remove the façade of the wellness, anti-aging, and beauty industry we must simply ask ourselves: what do these products do? Certainly, physical traits go in and out of style (the optimal size of eyebrows, breasts, butts changing every half-decade), but plenty stays exact the same. Has anyone ever gotten a nose job to make their nose bigger? Is there a single makeup product that enhances wrinkles and acne? Is there a mascara that makes your eyelashes shorter, a procedure that enhances the double chin, an undergarment that promises more stomach rolls? Not only are the physical goals of the beauty market the same as they always have been, the psychological goal is the same: to make you feel like you are making the correct choice.

It feels good to be beautiful. It feels good to know that other people think you are beautiful. There are monetary rewards, there are social rewards, there are psychological rewards. Visual proximity to Whiteness, to Cisness, to wealth, these things have a direct material impact on our lives. Our idea of beauty is not one naturally constructed; it is sold in magazines and movies and advertisements featuring one or more Hadids (Bella, who is Palestinian American, recently opened up about her regret over her nose job at 14, saying "I wish I had kept the nose of my ancestors”.) I don’t care to weigh in about what beauty is or isn’t, I’ll leave that to Oscar Wilde and Kafka and James Baldwin and Dorothy Parker, but I know that our conception of beauty is also not entirelysocially constructed. There is something so uniquely beautiful about the sixty year old women in the grocery store, the ones in felt clogs who fill their carts with organic arugula and and the ones in faux-fur coats and over-drawn lips whose voices rasp when they ask for a package of Marlboro Golds. There are college boys in Costco t-shirts bought by their mothers who, behind their rectangular, wire-frame glasses, possess the most beautiful eyes and eyelashes, thick and dark and pointing down like sweet old cows on dairy farms.

It is taboo to critique the concepts of makeup, cosmetic surgery, anti-aging, because it is received as “shaming” others’ “choices”. Why does there have to be shame? Critiques of these systems are not shaming others’ choices at all—they’re questioning the very idea of choice and of desire itself. An ad for an anti-aging product featuring a girl that looks no older than 16 advertises itself as the feminist alternative to botox because it is “non-invasive”. We see through our aesthetic Overton window, and this is the exact language and rhetoric that draws the curtains further and further closed. When the idea of aging naturally is fully removed from the conversation, it becomes self-care to prevent wrinkles, so long as you do it with these products marked with the correct trademarks.

Contemporary marketing operates by transforming fear into desire. The fear of lacking control, the fear of being unwanted, the fear of aging, the fear of being oppressed are all repacked as the need for growth. This growth is both individual (“self-care”, confidence, independence) and political (media representation, “disrupting” old industries). We know how little agency we have: we spend all day working either demeaning service positions or bullshit jobs, which we depend on to pay our ever-increasing rent to our ever-corporotizing landlords. Our voices are lost: journalism, art, and media are controlled by mega-monopolies. Voting is both necessary and meaningless, every election an existential choice between two largely identical parties. We feel like insignificant cogs in a Post-Fordist machine. What the wellness industry (and really, all consumer industries) offer is a feeling of action, a feeling of choice, a feeling of momentum. By purchasing a gua-sha roller or a dozen milliliters of Juvéderm, not only do we feel we are performing an act of personal empowerment, but we believe we are performing a political act of feminism.

Through wellness capitalism we are fulfilled by the act of consumption, one of very few actions we actually can take, but never pleased, because it is in the nature of the market to require its consumers to stay hungry, wanting, works-in-progress. These things may make us “feel good” but they are designed to ensure we never feel complete.

Perhaps Nina Power says it best in her 2009 book, One-Dimensional Woman:

“[Pop] Feminism offers you the latest deals in lifestyle improvement, from the bedroom to the boardroom, from guilt-free fucking to the innocent hop-skip all the way to the shopping mall - I don't diet so it's ok! I'm not deluded! I can buy what I like! Feminism™ is the perfect accompaniment to femme-capital™: Politics, such as it is, belongs to the well-balanced individual (the happy shopper), sassiness is like, so where it's at (consumer confidence) and, most of all, one must never, ever admit to cracks in the facade (ideology). This foundation is flawless! And it lasts all night! Unlike men, titter, titter, etc. etc.“

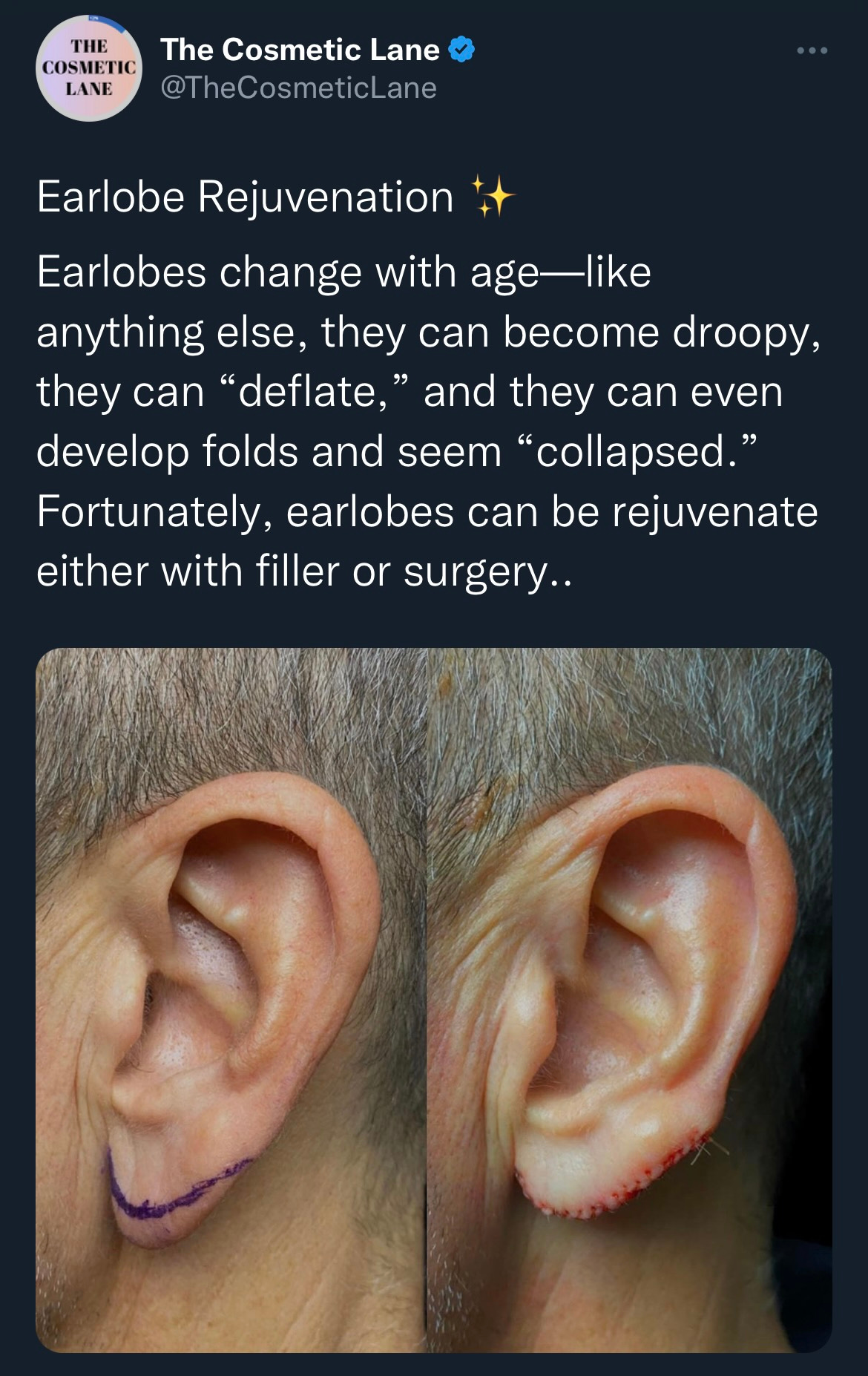

Do you think I can get my earlobes rejuvenated at Clarie’s?

in new york it seems like every empty storefront now houses a cosmetic dermatologist or new wellness brand. the more these ideas are “normalized,” the harder it is to exist in a “normal” body. people forget– though companies do not– that by changing our definition of normal, we shift our overton window. i love how you put that. i pass these stores and briefly i consider their promises; i’ve begun to vocally disavow them each time i walk by, if for no other reason than to remind myself that the eternal quest for youth and beauty is neither sustainable nor “normal.”

Something has always rubbed me the wrong way about Botox being a feminist statement. A cousin of mine works in fillers and injections and she frames it as empowering, which I suppose in STRICTLY the sense that it is a choice to make or not make it is empowering, but it is feeding this toxic cycle of a system that encourages women to literally change themselves just for aesthetic reasons. Literally inject and chop themselves up. All to be society's definition of prettier. Thanks, I hate it.

Skincare can be a bit more nebulous, I feel--on the one hand, I use skincare products, I put on sunscreen and moisturize. It makes sense to take care of your skin. On the other...when the quest of skincare is framed as "antiaging," when the goal is not gracefully growing but FREEZING your young and beautiful self, that's sooo toxic, and I thank you for pointing it out.

As you said: 60 year old women at the grocery store are so beautiful. Maybe we all grow to be like them: living, breathing, interesting, and lovely in our own way. ✨