Window Shopping with Liz Franczak

The TrueAnon cohost and culture war veteran talks commodity fetishism, mass shoppy shoppification, and dressing for court.

“All sorts of things in this world behave like mirrors.” —Jacques Lacan

“Maybe the best any of us can do is not to quit, play the hand we’ve been given, and accessorize the outfit we got.” —Carrie Bradshaw

Very few things feel rare on the internet. The digital world is a landfill of content, saturated with images, opinions, e-commerce, pornography, artistically neutered Bandcamp EPs, abandoned Geocities pages, Facebook albums of long-dead family pets. And yet, as our online (and arguably offline) selves stew in a dearth of mystique, Liz Franczak remains fashionably, refreshingly elusive. Franczak co-hosts the wildly popular podcast True Anon, but unlike many of her peers, she rarely appears in photos (but when she does, always looks effortlessly radiant) and generally dispatches Tweets no more than once a week. As a day-one True Anon listener, I’ve long been piqued by Franczak’s off-handed comments and asides on the podcast—throwaway references to Alexa Chung, Trey MacDougal, American Apparel—and I am beyond delighted to have had the pleasure to discuss the state of style today with the one and only Liz.

Liz! Hello and welcome! Thank you for popping into my corner of cyberspace! I’m sure many of my readers are familiar with your presence on True Anon, but for those that aren’t, I’d invite you to introduce yourself as you see fit.

Hello, hello! I’m Liz. I co-host a podcast called TrueAnon. I think our tagline is: a podcast about your enemies, made by your friends. We started the podcast almost four years ago, when Jeffrey Epstein was arrested. When we began we were focusing on that case — he was killed not too long after we started — and since then we’ve done episodes on everything from Elon Musk to AI to the Troubled Teen industry and the history of NATO. The show is basically whatever we want it to be, which is certainly a luxury.

The podcast itself largely focuses on politics, but some of your and your cohost’s interests make their way into the show. I always enjoy hearing your comments on basketball and style, though I’ll admit my only knowledge of the former is the uniforms of the 1992 Lithuanian Olympic team… I remember reading somewhere, ages ago, that you used to work as a vintage buyer for NastyGal and I’ve been curious about your experience ever since. Is there anything you’d want to share about your experience with that role, either its actual labor demands or the culture of 2010s Indie #Girlbossery?

Well, there are sort of two sides to this right? There’s the ‘working in vintage’ part, and then there is the ‘working at a start-up’ part. I worked at a vintage store for about seven years before working at NG, it’s how I knew Sophia, and when she was looking to hire someone to manage the vintage business for the first time since she handled it, she called me.

As far as ‘working in vintage’ or ‘being a vintage buyer’ — I think it’s a bit different than people might imagine it to be. I spent a lot of my time basically sifting through garbage, and I do mean literally garbage, like trash. Whether at people’s homes or, most often, at extremely sus warehouses in remote areas, digging through dumpsters full of clothing, pulling out shit and lugging huge bags of clothes around, messing up my back. It was pretty physically demanding but also mentally: deciding in a split second whether or not something will sell to someone and for what and how it could look on someone or how it will look on a website and styled on a model, etc etc. And having the confidence to make those choices extremely quickly and efficiently—just a very bizarre skill set to develop.

And doing all that was in stark contrast to the, as you call it, 2010s Indie #Girlbossery, or just the plain old startup vibes at the company. I didn’t fully fit in when I arrived, I’ll put it that way. I was intimidated by a lot of the women there, because I don’t think they really got me, and I never really got them. I had never had an “office” job before, or what felt like a “real job” before, which I was insecure about. I was all self-taught, basically self-educated. And I felt a lot of pressure—mostly self-inflicted I think—to assimilate: I was self-conscious of my role there, because I felt like a real outsider, doing this weird vintage thing that was sort of removed from the rest of the team. I was embarrassed by my lack of experience with a corporate job, really any kind of professional training. So I always felt a bit removed from the whole enterprise. But I think a lot of people there, especially in the early years, in creative positions, felt that way. It was a real rag-tag team for a minute.

All of it hit a fever pitch after the book and all the rest. I think everyone knows the story of the company. It was definitely a moment. But I’m still best friends with some of the girls I met there.

That’s super interesting—I want to circle back to that idea of clothing as “stuff,” but before that… Your work with True Anon takes a very historical materialist approach to contemporary politics and rhetoric, which I think is great grounding for the show’s broader examination of histories of power. There is so much to say about the fashion and textile (and broader consumer goods) industry and its environmental and labor impact, but I want to center our conversation on the relationship between aesthetics and political economy. You’ve been on tour recently and seen a lot of the country. Of course, there is never a single dominating look but multiple simultaneous trends; what ideas or motifs are you seeing a lot of, both in big cities and more suburban environments? Where do you think these trends are coming from?

I don’t know if I saw much of anything on tour! It is true what touring bands say about never really knowing where you are. I honestly can’t tell if that was because of our schedule or because so much of America, when you are on tour, looks the same. I never saw anything of any city, it was very fly in/fly out, drive in/drive out. But the internet can be of great use here, less so at the level of micro trend forecasting and more so on the level of social interaction and behaviors.

The most singular development in the 20th century in America is the dominance of the middle class — and yet we still go to great lengths to deny its existence and influence, even as the American middle class and its consumption tastes and patterns power the globe. I think when you live in a middle class dominated society (as in, who drives the trends, consumer preferences, tastes, and so on) consumer goods dominate any and all discussions of culture. We look to these moments to tell us something deeper, as if Ben Affleck making a movie about sneakers is some great social disclosure, or HBO’s latest offering has Something To Tell Us About _____ and so forth, all of it warranting a series of theses. Thems the breaks when you live in a consumer capitalist system, I guess.

I think most people have a love/hate relationship with this. I certainly do! And not just creators but increasingly everyone, now that we all get paid in likes and subscribes and follows. I think we all subconsciously understand that to someone, somewhere, our attention has value, (or maybe we simply think it should, since we see other people’s attention certainly does) and we can withdraw that in protest or deploy it to show support. We are all sort of in the throes of this thing, which commands us to comment and create more content for other people to comment on, like one big social-cultural cottage industry. When you start to carve out the shape of this thing, it makes sense that all cultural production feels so recursive. How could it be otherwise?

It can certainly feel like we’re all passengers on some commercial vessel riding the Trend Waves, which becomes much more stressful when the focus moves from clothes to our actual, physical bodies. Certain body types are seen as trendy (though never straying outside of certain parameters, like a degree of thinness), and it seems like the era of volume (BBLs, lip fillers, etc) is ending as waifishness and gauntness once again return. Why do you think this is? Is it just the passage of time, or is it tied to something more?

There is always a pendulum swing, no? The excesses of one trend spark the reaction of the next. There’s obviously other dimensions to this, it isn’t that simple. Advancements in plastic surgery and non-surgical interventions shaped (no pun intended) the BBL/Filler craze, and the same of semaglutide treatments like Ozembic. Medspas are something like a $5.5B industry in America and growing.

I’m sort of obsessed with the beauty industry—not just because I do love a good serum but because it really has grown so so so much in the past ten, fifteen years. And it’s projected to get even larger. There’s obviously a huge correlation between the rise of HD cameras and the proliferation of lasers, the glass skin trend and so on. Everything is just so smooth now. It’s like we can’t tolerate friction, which I think eerily mirrors a lot of our experience with and expectation of social media and interactive technology, and in general, our inability to handle things that make us feel uncomfortable.

I don’t think there is just one easy answer for these shifts in taste, how much we are control of what we chase after and objectify, particularly when it comes to bodies and faces and especially now that everyone from toddlers to your random aunt are so thoroughly mediatized—all these changes feel much more fractal than linear, a bit more hectic, unpredictable and schizo.

Shifting gears a bit: the voice of what is “stylish” (as well as what is “trashy” or “unchic”) comes from many places—fashion magazines, designers, celebrities, artists, influencers, the public, nostalgia… do you think that we’re headed towards a more democratized idea of taste, or do new channels of influence just obscure the mechanisms of the Culture Industry?

I think we live in an era of democratized taste. This was sort of Virgil [Abloh]’s whole thing, no? Everyone can make a brand, here you go. I think this is empowering and freeing to a lot of people. The avenues are there, to ‘make something happen’ if you will. Just look at the rise in small business owners! It’s not just the tax system that incentivizes it.

I also think it results in the production of a lot of mediocre shit. How could it not? And more than that just tons more shit. We produce so much. Just so much, and so much useless shit, useless content, useless noise, useless everything. It’s sort of hard to think about, it makes me feel dizzy and a bit sick, the sheer amount of shit we are producing and uploading every day. Is this a good thing? I don’t know.

Is there any way for fashion and style to be subversive, or does everything become recuperated into marketplace machinery?

I don’t know. One thing working in vintage taught me was to not be too precious about things. When you go through 200-300 things a day, you see a lot of stuff—some really, truly amazing things and a ton of garbage just the same. You see it come in and go out, come in and go out and you just sort of get used to not being super precious about things.

At the same time, I love things. I love old things, old books, old houses, old clothes. I spent years in high school searching eBay for early McQueen and Galliano and convincing myself I was going to be a fashion designer. eBay was good back then (lol). I love tailored clothing and well made furniture and good food—I am very much a Libra rising/Taurus sun—but I am also extremely embarrassed by all of this and conflicted.

On the one hand, my experience with vintage, I think, can lead to overconsumption, cycling through shit and being reckless, which I think I am guilty of. On the flip side though, I’m super conscious of this image of the collector—I guess now in the digital era we call people curators, a term I loathe. I don’t ever want to be some bourgeois hoarder of trinkets, living in a museum of my commodities, just me and my things. I really don’t want to be a person of things. I’m still trying to figure out how to split the difference.

We’re producing more unneeded clothing, accessories, “stuff”, than ever, but their visual characteristics still feel tied to the material and economic world. The “hemline index,” which theorizes that hemlines get longer as unemployment and cost of living rise and get shorter when economic conditions stabilize, was introduced over one hundred years ago. Plenty has been said about the relationship between style movements like cottagecore and its almost Jeffersonian ideals, but few inquests have been made into the relationship between style and transforming economic systems themselves—finance capital, cryptocurrency, gig economies—how do you think that speculation and precarity have affected trends? What are the visuals of this new political economy?

I was in Nordstrom and they had one of those Ettore Stotsass mirrors, the pink squiggle one. I’m so tired of that fucking mirror. I feel like I’m staring into a TikTok when I look at it, like the mirror comes preloaded with a filter, so when I look at my reflection I’ll see some instagram version of me, I’ll see myself as a post. Like a fucking digital funhouse mirror freak show.

It’s funny, Nordstrom had all this stuff — they had so much stuff! So much novelty everywhere! Things absolutely no one asked for like fuzzy purses with tattoo embroidery and jelly bean jacquemus purses made for posting. Just the most obvious dumb shit. But weirdly, no size runs of anything. And this isn’t just the case at Nordstrom, there’s a lot of places that just do not have the things you are looking for. Doesn’t matter if it is luxury or high-street or the grocery store or a car dealership. Like we don’t even have the commodities for us to buy. But there’s new, always new, always more and more new.

A lot of people have written about/remarked on the ‘micro-trend’ phenomenon, especially during the post-Covid, TikTok frothy euphoria of 2020-2022. Danish Tulips as Dyson Airwraps and so on. Social media has increased the speed at which these things circulate so much and are consequently produced and just-in-time demanded. Truly the annihilation of space over time.

I think that’s really interesting—I wrote about this phenomenon of plastic objets as signifiers-of-taste in an earlier piece about Instagram Store Core home decor—and I think the sort of aesthetic meaninglessness of consumer goods does really reflect the emptiness of a gig economy. Everything is perfunctory, disposable, replaceable, lacking in any specificity but just sort of gesturing at whatever amount of “personality” that will satiate consumer desires. At the risk of sounding like a hippie or a knock-off Marianne Williamson, there is something that feels… spiritually devoid? about adorning ourselves and our homes with items that are “stuff,” made to be bought and not used, before being “clothing” or “decor”. Commodity fetishism has this internal snowballing effect that comes from the aesthetic homogenization capital produces; as markets dictate exploitative labor practices and deregulation, commodities lose their specificity and charm and, really, their humanity--it then becomes so much easier to believe that these things simply come from nowhere and will go nowhere after they are disposed. I don’t know if there’s a direct question in here, but I wonder if this sense of spiritual impotence of style resonates with you.

I’m curious what you would include in ‘style’ here — when I think of our, like, consumer self, our consumer being, I think okay, yeah, it is the things we buy, but more often it’s the things we ‘like,’ the things we post, the jpegs and videos we catalog or (as they say) curate away. Everyone is so obsessed with vibes, the ambient feelings that we cull for ourselves. It’s the interactions we have online, the people we follow, the topics we engage in, the content we consume, the content we produce. It’s difficult to weed out what is and isn’t a ‘commodity’ proper here, which is to say, it’s all commodities all the way down.

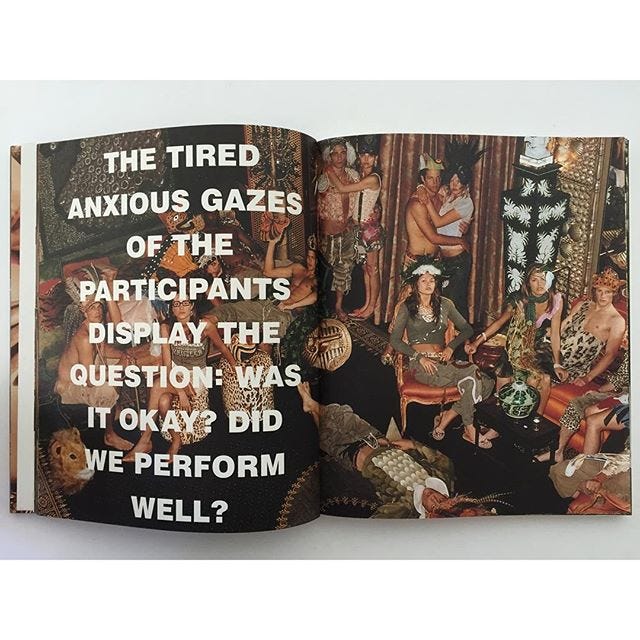

And when we talk about the anxieties of consumer capitalism, and especially this form of it, I think what we are constantly running up against is the impossible “problem” of identity, or the impossibility of finding a solution to it: we are sold these so-called avenues of self-discovery and self-formation, social media platforms as tools of creation and expression and discovery (most with a ‘buy it now’ button built in). But really what they offer is a narrowing rather than an expanding of the self—into something extremely narcissistic, reductive, compliant, and dependent on recognition and reassurance from anyone and everyone; a self that relies on constant feedback—through likes, comments, mentions, etc but also on reflections of ourselves and our consumer lifestyle choices (what we know call our identity), a sort of social security-blanket. But I think it just produces more anxiety, confusion, self-doubt and yeah, that feeling of ‘spiritual impotence’ as you say.

Not to be corny but we all contain multitudes, which means contradictory and contestable forms, memories, ideas, etc., most of the time hidden even to ourselves. I know I keep bringing our conversation back to technology, but I think it’s really important. There’s no outside this stuff, especially when we are talking about the current and future prospects of consumption practices. Social media, predictive algos, all of it, stopped being voluntary a long time ago, and I’d argue it never really was.

Clothing isn’t the only outlet for fashion and style trends—home design and graphic design are just as susceptible to trend cycles and aesthetics with fundamentally political undertones. Brad Tromel is always great at identifying and decoding these looks, but I’d love to get your read on it, too. Are we finally leaving the sans serif purgatory we’ve been trapped in? And what feeling is millennial and gen-z marketing trying to tap into aesthetically?

I think we left the Blank Sans Serif style behind a while ago! Now everything is very ornate. It’s Ghia x Flamingo produced sober tinned fish imported from portugal, exclusive to Gah Shoppy Shopperies. Tide goes in, tide goes out. I look forward to everyone getting back into mid-century furniture once they are tired of the British paint-flooded walls and Deco inflected maximal print interiors.

I’m not sure gen-z marketing people know what they are trying to tap into aesthetically. Do they even talk to gen-z kids? Almost everything feels geared toward millennials, even when it isn’t meant to be, because it’s all millennials making the decisions. I don’t think this is even that unique to gen-z or millennials. Euphoria is a great example of this. It’s a tv show about gen-z, made by millennials to flatter millennials. It’s gen-z safari. That’s ok, but we don’t need to pretend it’s some revealed social truth. Unless we’ve got some more content to make.

It definitely seems like advertising is completely geared towards millennials, even for products that are geared towards different demographics—though I must admit I am horribly protective over my tastes and hate to see the things I love trend and then manifest in mass-market imitations in H&M Home… But I digress. The messy-chic squiggly line moment does seem to reflect a desire for things that feel handmade and local, even when they’re not, and perhaps overall less “clean” than the sleek Helveticas of their predecessors. To me, it seems like a lot of people want this slowness and connection, even though that desire is often satisfied with mass-produced Just More Stuff. There is, perhaps, optimistic sweetness to this, one that I am often (by my own admission) too cynical to see. To conclude on a more upbeat note, I’d love to know if there’s anything you’re doing in your own life that is slow or inconveniently laborious or imperfect or antiquated that feels meaningful and real to you. :)

I’m sorry to be so downbeat! I don’t consider myself a negative person, but I think “appropriate cynicism” is probably apt. It’s always good to be realistic about things.

I spend way too much of my time gardening and I love it. I recently planted a couple rose bushes — my mom was a big gardener, but I never really took to it until I moved into the place I’m at now. I’ve got all these guys planted, peonies, lavender, we have a big strawberry patch going, some dahlias that I’m waiting on, and I am currently on aphid duty every morning with the roses. I like to take my coffee outside and go around and check all my little guys. It’s very nice to get back into working with my hands.

Fast & Silly Questions:

Film(s)/television programs or characters with iconic style?

There’s too many to mention. I’m always cycling through. Right now I’m on a big “East Coast Summer” tip so I’m feeling some classic Joey Potter Capeside vibes. I should probably dig out my old copies of A&F Quarterly.

The oldest thing in your closet that you still regularly wear?

Oldest as in age or oldest as in thing I’ve had the longest? I think my robe is the oldest? It’s a like, turn of the century/1910s silk kimono type thing, with painted flowers. It’s totally rotted but you gotta just wear these things until they shred off of you. I’m not sure about the thing I’ve had the longest. I have an old Balenciaga moto bag that I just can’t part with but also feel a bit RealReal-Zoomer wearing it—it’s really early, back when the line was called Le Dix. I was a Ghesquiere obsessed teen.

Least favorite recent trend(s)?

Just because you can get that vintage purse from the 2000s doesn’t mean you should.

Favorite style movement(s) or niches throughout history?

I really like moments where old decades are interpreting trends from previous decades. So like, those garish ugly prints from the 90s when they were doing the 60s. I mean, I hate them, but I think tracking down and identifying those moments is really fun. 1970s doing the 1930s is great.

This is super niche but there’s this little enclave of resort brands from the early 1970s that I really love — they are called like, St. Tropez and things like that. It’s all very gauzy, glitzy, bohemian sets. The pants always fit great and the color palette is always lovely, like warm and dusty and sandy. It is not really my vibe or what I wear, but I love them.

Which figure that you’ve covered on True Anon has been the best dressed?

Gotta be one of the housewives. Alex McCord, and Simon of course.

Next big cosmetic surgery trend?

My understanding with the tech is that it’s really just all about Lasers. Lasers Lasers Lasers. I also think mini face lifts are going to get more popular now that people are turning against all the volume— I don’t know how I feel about that—lower lifts are becoming more popular with younger people, and influencer types are foregoing injectables for minimal surgeries (implants, lower lifts, blephs, etc).

Practicality or whimsy?

Practicality.

You and your co-hosts sat in the courthouse to give day-by-day coverage of the Ghislaine Maxwell trial. How do you dress for the courtroom? What was your favorite courtroom look? How do you dress for the courtside??

Omg as if I’ve ever sat or will ever sit courtside. That would be very cool and insane. I can’t imagine seeing a game that close. Whenever I go to a game, I feel like I’m watching a bunch of giants run around, I can’t imagine seeing someone like KD three feet in front of me. You forget how tall these guys are when you are just watching them on TV all the time.

When we covered Ghislaine Maxwell’s trial it was December and also it was super strict Covid time, which put a damper on any kind of real outfit planning. In my head it was very Ally McBeal — David E. Kelly always “understood the assignment” (apologies). It was 1000% less glamorous than that but I do love a turtleneck and a sensible separate!

![TOMT] A blog/archive of 1960's/1970's medieval aesthetic? : r/tipofmytongue TOMT] A blog/archive of 1960's/1970's medieval aesthetic? : r/tipofmytongue](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Igbf!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F05d15a1c-279a-48ed-9ec0-fab5a6920353_540x777.jpeg)