Everyone Is Grotesque and No One Is Turned On

Strange, uncanny, and confrontational depictions of sex in film are needed now more than ever.

Here is a controversial belief I hold: there are too many unnecessary sex scenes in movies these days. I think. I’ll admit: I am a yuppie snob and I tend to watch far more old movies than new ones, and I rarely see current high-budget, major studio films unless they are fascinatingly ridiculous or terrible (on a related note, does anyone want to see M3GAN with me this weekend?). But from what I have seen, the sex scene in contemporary American mass-market filmmaking has become a rehearsed, blandly necessary staple that serves no discernible purpose beyond mashing the bodies of our A-List stars together like naked Barbie dolls.

Why do we show sex in film? Most obviously, perhaps, in commercial film there is an appeal to seeing beautiful people gyrate under soft lighting, or a voyeuristic desire to see the well-known celebrity in a unique (and constructed) position of intimacy. A sex scene can be payoff for budding romantic tension, the climax (in both senses) of a story arc between two people. Many period pieces, chic flicks, and superhero movies of vastly varying quality favour this treatment of sex and sexuality. But of course, we also know that sex is never just sex, especially as subject of artistic depiction. Now cliché but ever-relevant, it is Oscar Wilde who was first attributed with saying “Everything in the world is about sex except sex. Sex is about power.” In art, as in life, sex is rarely just the expression of physical attraction between two people; it is about power dynamics both interpersonal and structural, desire, the body, repression, expression, boundaries, violence, history, taboo, memory, and practically all the other great and literary ideas we grapple with every day.

In R.S. Benedict’s seminal 2021 essay, “Everyone is Beautiful and No One Is Horny”, the author unpacks why our film output is so sanitized and sexless. If we could control our bodies, we could control our minds, and if we could control our minds, we could control our future—a comforting notion as we wallow in the deep End of History. Our art (at least, our industrially-made art) is no longer erotic because it is actively opposed to the animalism of carnal desire. Benedict writes about the loss of true eroticism in film and the embrace of blandness, but there is another presentation of sexuality just as valuable—and just as rare—as the erotic: the strange.

Some of the greatest sex scenes in American film are strange and uncomfortable and confrontational. To be clear, I don’t mean scenes that depict sexual violence or questionable consent--for comprehensive, articulate, and empathetic writing about depictions of rape on screen, I highly recommend Ira Beare’s “not only will i stare”. Rather, why is sex such an important vehicle for producing weird and the eerie? Philosopher Mark Fisher defines these concepts as “allow[ing] us to see the inside from the perspective of the outside” often by the “conjoining of two or more things which do not belong together”—how does the conjoining of two (or more) bodies allow us to see the inside, the outside, and the many things between?

Sex as (Re)Production

Films like Boogie Nights (1997), Election (1999), and The Brown Bunny (2003) depict sex that is meant to be unerotic, confrontational in its matter-of-factness. Not only is the physical choreography of sex matter-of-fact, but so is its artistic stylization (simple angles, restrained lighting, limited sound design).

All three films depict sex as production: in Boogie Nights as the production of entertainment, in Election as the production of a family, in The Brown Bunny as meta-production (the film’s reputation rests almost entirely on a three-and-a-half minute long unsimulated blowjob scene, mentally inseparable from the film’s writer, director, producer, and star, Vincent Gallo and his co-star Chloë Sevigny). The characters in these sex scenes want something other than sex, they want something other than each other. In these contexts, sex functions as an action performed by an individual to produce a desired result (fame, purpose, and forgiveness, respectively), thus an unerotic approach to filmmaking is taken. We are uncomfortable with such utilitarian approaches to sex because we don’t want to believe that we (and certainly not the people we’re sleeping with) are having sex for unromantic, unsexy reasons.

Not only does sex a matter of production in these films, it is a matter of re-production. In Boogie Nights, the adult film industry is exploding because of the release of home video, to be replayed over and over by consumers within their own homes. In Election, the production of a baby will (as Jim McAllister believes) re-produce the sense of purpose lost with he enters middle age. In The Brown Bunny, the blowjob re-produces a dead woman, reanimating her for so that her ex-boyfriend may find closure despite his own moral failing. And of course, all of these films—released within six years of each other—are films; they were made to be reproduced and distributed to mass audiences. The “unstylized” sex scene is a conscious artistic choice, one meant to evoke the banality and function of consumer products, uncomfortably extracting eroticism from sex—and life—to fulfill an unfillable desire.

The Orgy

The term “orgy” carries with it a sort of grotesque character, often implying some sort of bacchanalian excess. Its usage does not always mean a literal sex act but it is always sexual, a multitude of overlapping things, shiny and twisting their limbs. The individual is subsumed by the group, but the group is elevated to a single, almost divine being. Two of cinema’s greatest orgies capitalize on these associations: Eyes Wide Shut (1999) and Society (1989). In both films, we—like the protagonist—have begun watching a private ritual. It has its rules and structures that we do not fully understand but its participants know intimately. There is a joining of a group of people and one thing is clear: we do not belong here; this pleasure is not ours.

In Eyes Wide Shut, the orgy is pristine and rehearsed, its participants deliver an expertly restrained performance. In Society, the orgy is the opposite: an expression of hunger, reverting to the primal, allowing the body to act on behalf of its desires. The hostile orgy of cinema becomes an obvious vehicle for class commentary as we watch a group of people indulge themselves in an excess of both psychical and psychological pleasure: a sense of exclusivity, a sense of being the best, a sense of existing outside of social norms. The camera, and thus the audience, disrupts the clandestine ritual with its gaze. Not only are we seeing something that is “wrong”,1 we are doing something wrong by witnessing it, we have become guilty of the same over-consumed decadence on screen.

Confrontational Sexuality

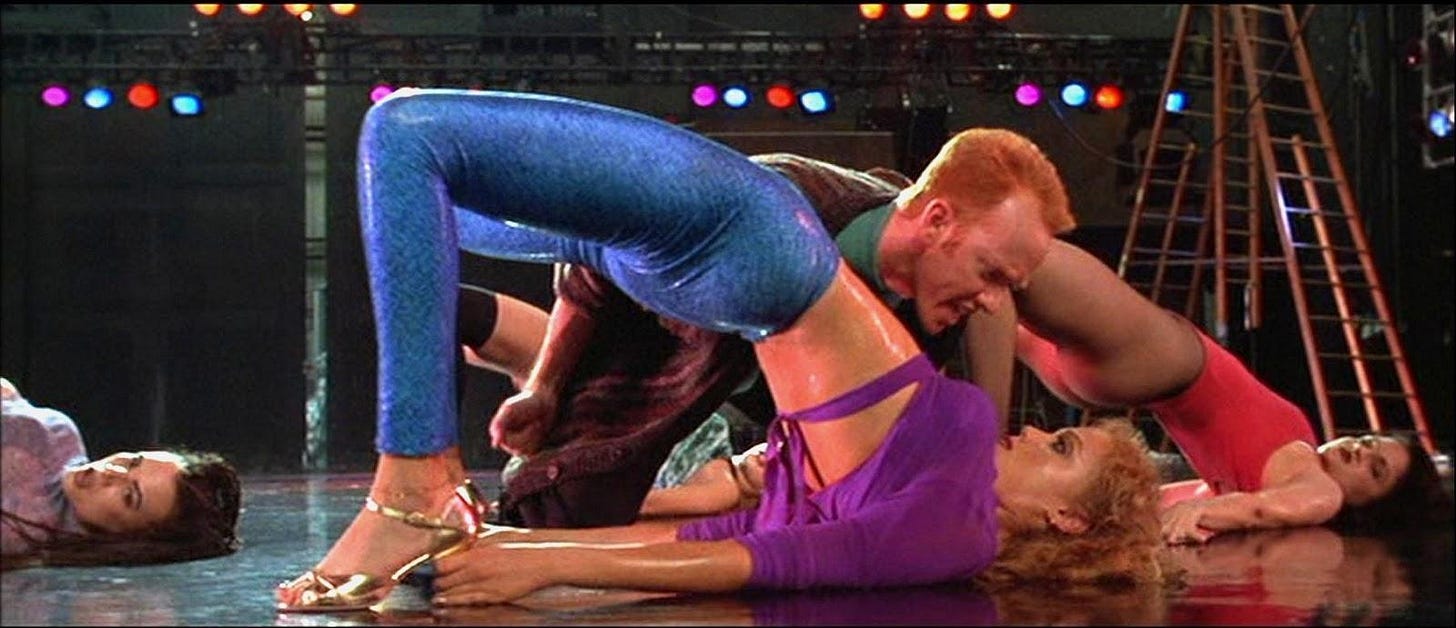

There is a type of sex scene in film that can really only be described as strange. Sometimes the strangeness is obvious, sometimes it is impossibly hard to define. One very strange sex scene takes place in Showgirls (1995), a film critically panned at the time of its release but ripe for reconsideration as far more complex than the sexploitation romp it was marketed as. Showgirls was directed by Paul Verhoeven, depicting a wayward young woman moving through a sleazy, corrupting environment of sexuality and excess. Showgirls was sold to mass-market audiences as sexy and fun and risqué, rather than as art film by an experimental filmmaker. The film would be regularly critiqued as “exhausting”—an apt descriptor that reveals the success of these films in creating immersive, confrontational experiences for audiences.

In Showgirls, our sex scene begins with former Saved By The Bell star Elizabeth Berkley’s character, Nomi, entering a Las Vegas pool, followed closely by the magnetic and utterly inscrutable Kyle MacLachlan. Underscored by classical music and warm lighting, there is an air of romance to the scene and its beautiful leads. But something strange happens: as intercourse begins, Berkley’s body starts to make strange movements best described as writhing. It’s almost unhuman, not animal or robotic, perhaps alien. There is something so obviously performative about Berkley’s delivery, in line with her character’s aspirations to become a Las Vegas showgirl, that stirs this discomfort. Who is she performing for? Is she performing for her partner? For herself? For us? The job of the showgirl is to sell a fantasy of access to beautiful, expertly posed women. Not only must the showgirl sell this fantasy, but she must sell the idea that she enjoys it and receives pleasure from her audience, fulfilling their desire to be active, “successful” lovers. We are not only Nomi’s audience but also Berkley’s; her role in Showgirls stood in direct contrast to her image as a clean-cut network television teen star. Berkley’s participation in the film was framed as both corrupting and liberating, depending on the source, and as witness to her participation the audience becomes the force active in either corrupting or liberating her. In this scene, is unclear if Nomi (and Berkley) is so immersed in genuine passion that she has lost all control in her body or if she is so focused on her performance she has lost all sense of the erotic; it is this paradoxical state of being that disorients the viewer.

Artists, Audiences, Producers, Consumers, Subjects, and Objects

Film is a medium defined by its production. To make a film is to produce, capture, and record audio and visual information. The distinction in storytelling between theatre and film is vast: theatre audiences have the power to gaze at the stage and its characters as they wish, unlike the camera, which controls the act of looking in a much more active way. Theatre is ephemeral and moves in one direction, always starting, ending, and then being finished. A film, of course, begins and ends, but it can also be replayed, rewound, restarted, fixed to depict the exact same information in perpetuity.

We think of sex as something that is organic, messy, and intimate. We want sex to be an expression of animalistic or romantic desire, a ritual between its participants. Sex on film can never be sex in real life because the act of filmmaking makes “authentic” or “realistic” sex impossible. Part of the reason we’ve lost our sense of eroticism in film is because we’ve industrialized its production; a handful of studios pump out tightly controlled films designed to access as wide of an audience—no, market—as possible. In this labour environment there is no space for spontaneity or humanity or personality, all of the aspects of artistry that mirror sexuality.

Strange sex on film embraces the complex relationship between sexuality and production, instead fully embracing it. We want to believe sex is expression, particularly the expression of some larger, intangible feeling. We also know that our idealized conceptions of sex and sexuality aren’t congruent with its actual practice; it can be a performance or a tool or an expression of insecurity or jealousy. Seeing sexuality expressed in its unidealized form reminds us that our own sexuality is far more complex than we’d like it to be, a reminder that evokes a feeling of confrontation and discomfort within ourselves.

Perhaps the most inherently uncanny, discomforting aspect of sex on film is the presence of the camera. Most people believe that sex is a private activity. Most sex takes place privately. Most sex is conducted in enclosed spaces with no witnesses but the participants. In polite society, to watch other people have sex is considered not only rude but sexually perverse. When people talk about finding most sex scenes “uncomfortable”, I think their feelings are largely responding to the social expectation that watching other people have sex is wrong.2 Watching a film is, itself, an act of voyeurism; we’re able to witness in detail the lives and the emotions of others without being watched ourselves. This is the great joy and importance of fiction (and ethical non-fiction), the understanding that what we are interacting with has been given to us, for us, by an outside voice. Sharing art is an act of intimacy.

The sex scene reminds us that we are accessing someone else’s narrative, in a way that may be intentionally or unintentionally uncomfortable. And the things that remind us that we are audiences, gazing at our subjects in turn remind us that we are also subjects who are gazed upon.

When filmmakers successfully evoke the uncanny, the strange, and the uncomfortable--particularly in regard to sexuality--something remarkably valuable happens. We are stirred by films in this way because they are immersive and because we have given ourselves to the experience of engaging with art. At the same time, we become hyper-conscious of our position as an audience, of the artifice of filmmaking, of the construction of what we see. Not only do discomforting displays of sexuality allow us to examine larger political or artistic themes, they also allow us to connect with ourselves and each other in uniquely profound ways. ❦

Author’s note: I have chosen to focus on only American filmmaking for this essay—for European films that have compelling and strange depictions of sexuality (though I wouldn’t call all of them “good films”), I’d recommend Titane, Raw, Possession, Calligula, Romance, and Nymphomaniac.

I’m sure there are many other films that could fit in this article, I ended up cutting a few myself for clarity (sorry, Spring Breakers!), so please feel free to suggest some in the comments! Especially international film from outside of Europe, pre-1980s film, and film depicting or created by people from marginalized backgrounds.

Though, of course, the real-life action of the orgy has no inherent moral value, good or bad.

Blah blah blah same caveat again that I am not trying to make a value judgement on consensual voyeurism

![It Came From the '80s] The Gooey Grand Surreal Shunting of 'Society' - Bloody Disgusting It Came From the '80s] The Gooey Grand Surreal Shunting of 'Society' - Bloody Disgusting](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!jmeb!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fd810e737-38f0-4c12-9155-8ebf4448e237_740x512.jpeg)

Dog tooth has very bland, unsexy and eerie sex scenes!!

I’ve been thinking about the place of real sex on fictional movies, such as lust and caution dont really have a consensus about it yet