Mattel, Malibu Stacy, and the Dialectics of the Barbie Polemic

Our recent embrace of Barbie as a feminist icon leaves out decades of discourse about womanhood and consumerism. One episode of The Simpsons may offer the perfect response.

“Come on, Stacy. I've waited my whole life to hear you speak. Don't you have anything relevant to say?” -Lisa Simpson

“Don't ask me, I'm just a girl!” -Malibu Stacy

When I tell people my parents were forty-five when I was born, the usual response is: “That makes a lot of sense.” There are a handful of side effects that come with having older, second-wave feminist baby boomer parents; mainly being very good at talking to adults, building a vocabulary by overhearing backseat NPR broadcasts, and childhood bans on all things deemed “bad for women” or “consumerist.” In our house, there were no Disney princesses, no Uggs, and certainly, absolutely no Barbies.1 I know plenty of people my age with similar upbringings whose form of rebellion against their parents was dressing in hot pink and sequins and dosing themselves with Bath and Body Works Cherry Blossom body spray, but in all honesty, that was never me. I wore my suede Keens, cut my hair short, and called the pretty girls who couldn’t read chapter books “airheads” behind their backs. And to their faces.2

Naturally, I was a very opinionated—and almost certainly very annoying—child. I’ve been a vegetarian since I met my first cow at age seven. My childhood hero was Rachel Carson. And when Mrs. Wheeler’s fifth-grade class was tasked with writing opinion essays, as my peers opined papers about school uniforms and saving polar bears, I delivered a piece on the usage of prison labor in Walmart’s supply chain, making my family promise to boycott the brand. I’m sure it was unbearable. In other words, I was, and remain, a total Lisa Simpson.

Video from “Lisa vs. Malibu Stacy,” The Simpsons, Season 5, Episode 14. 1994.

If Greta Gerwig’s Barbie lives up to anticipation when it is released this July, it will become a generation-defining depiction of a brand that took in $1.7 billion dollars in profit last year. A quick Google search for “barbie feminist icon” revealed many, many, many, many, many articles lauding Barbie (full name Barbara Millicent Roberts) as a beacon of women’s empowerment. I’m certainly excited for Barbie; it looks fun and silly with a fantastic cast and a wardrobe to die for, but I’m not ready to buy Ms. Roberts’s liberatory power quite yet. Our contemporary Barbie Revisionism is lacking something, something perhaps best addressed by the last great Barbie Polemic, the fourteenth episode of the fifth season of The Simpsons: “Lisa vs. Malibu Stacy.”

“Lisa vs. Malibu Stacy” is a relatively simple, toned-down episode of The Simpsons. Lisa receives a talking Malibu Stacy doll (our clear Barbie stand-in), but is shocked to find that Stacy only speaks in antiquated, demeaning quips. She sets out to create her own doll with the help of Malibu Stacy founder Stacy Lovell, a doll who will have “the wisdom of Gertrude Stein and the wit of Cathy Guisewite, the tenacity of Nina Totenberg, and the common sense of Elizabeth Cady Stanton! And to top it off, the down-to-earth good looks of Eleanor Roosevelt.” Lisa’s new doll, Lisa Lionheart, and its sudden popularity pose a threat to the makers of Malibu Stacy, but they’re able to condemn Lisa’s doll to total irrelevance by simply introducing a new Malibu Stacy, this time wearing a little hat.

The episode was written largely in reference to the Teen Talk Barbie controversy of 1992, which occurred two years before the episode’s release in 1994. This Barbie doll came pre-programmed with four randomly selected phrases out of 270 possible phrases; most of which were harmless (“I love barbeques!” “Let’s make some new friends!” “I’m going to be a veterinarian!”), some of which were questionable (“I love shopping!” “Want to go shopping?” “Meet me at the mall!”), and one which caused quite the stir: “Math class is hard!” The episode also makes passing reference to the Barbie Liberation Organization (BLO), a feminist action group who swapped the voice recordings of Teen Talk Barbies with G.I. Joes and put both dolls back on the shelves for consumers to bring home. While parents were horrified to hear Barbie say things like, “No escape! Vengeance is mine!” followed by gunshot noises, kids didn’t seem to mind; when describing a G.I. Joe with a Barbie voicebox, one young girl said, “I like it because it isn’t so violent, it makes it more funny.”

What is so interesting about “Lisa vs. Malibu Stacy” is that it doesn’t take the anti-Barbie stance one would expect from a Lisa-centric episode; Lisa wants a Malibu Stacy doll. She owns dolls, she doesn’t think they’re inherently frivolous—she stages her own dolls to form a model UN. Much like Barbie, Malibu Stacy is a very employed woman, and when Lisa enters the Valley Of The Dolls (har har) section of the toy store, you see Stacy as a country music star and a stand up comedian… though these iterations are relegated to the bargain bin. When Lisa begins her crusade against the Malibu Stacy corporation, she mostly just wants an apology. She knows the role these dolls play in shaping girls’ identities, and she knows they can be used as a tool of empowerment. In fact, when she meets Stacy Lovell, the Malibu Stacy founder offers almost immediate assistance on Lisa’s quest. The meta-stance of The Simpsons episode is not that Malibu Stacy—Barbie—is a misogynistic object, but that her misogyny is part of her brand identity, one that the all-male board of directors at Malibu Stacy headquarters isn’t willing to part with. Misogyny is not so much the issue of Malibu Stacy but the vehicle through which the company is able to push its real moral agenda: consumerism.

Lisa, criticized throughout this episode (and most others) for her cynicism, ends the episode optimistically when she sees one girl choose Lisa Lionheart over Malibu Stacy. “You know, if we get through to just that one little girl, it'll all be worth it!” But it is now her optimism that must be shot down, as Stacy Lovell retorts the episode’s final line: “Yes. Particularly if that little girl happens to pay $46,000 for that doll.” Lisa Lionheart is not defeated in the marketplace of ideas, but in a much more simple marketplace: the mall.

“Lisa vs. Malibu Stacy” touches on so many of the themes people want to find in Greta Gerwig’s forthcoming film: feminism, girlhood, empowerment, the power of iconography, the relationship between objects, their makers, and their audiences… but its central theme addresses an issue largely missing from our discussion of the Barbie film—the issue of teaching consumerism.

The 2023 Barbie film is a commercial. I’m sure it will be fun, funny, delightful, and engaging. I will watch it, and I’ll probably even dress up to go to the theater. Barbie is also a film made by Mattel using their intellectual property to promote their brand. Not only is there no large public criticism of this reality, there seems to be no spoken awareness of it at all. I’m sure most people know that Barbie is a brand, and most people are smart enough to know this and enjoy the film without immediately driving to Target to buy a new Barbie doll. After all, advertising is everywhere, and in our media landscape of dubiously disclosed User Generated Content and advertorials, at least Barbie is transparently related to its creator. But to passively accept this reality is to celebrate not women or icons or auteurs, but corporations and the idea of advertising itself. Public discourse around Barbie does not re-contextualize the toy or the brand, but in fact serves the actual, higher purpose of Barbie™: to teach us to love branding, marketing, and being consumers. Take, for example, this tweet that is based on the assumption that the Barbie film is paying brands to do corporate tie-ins:

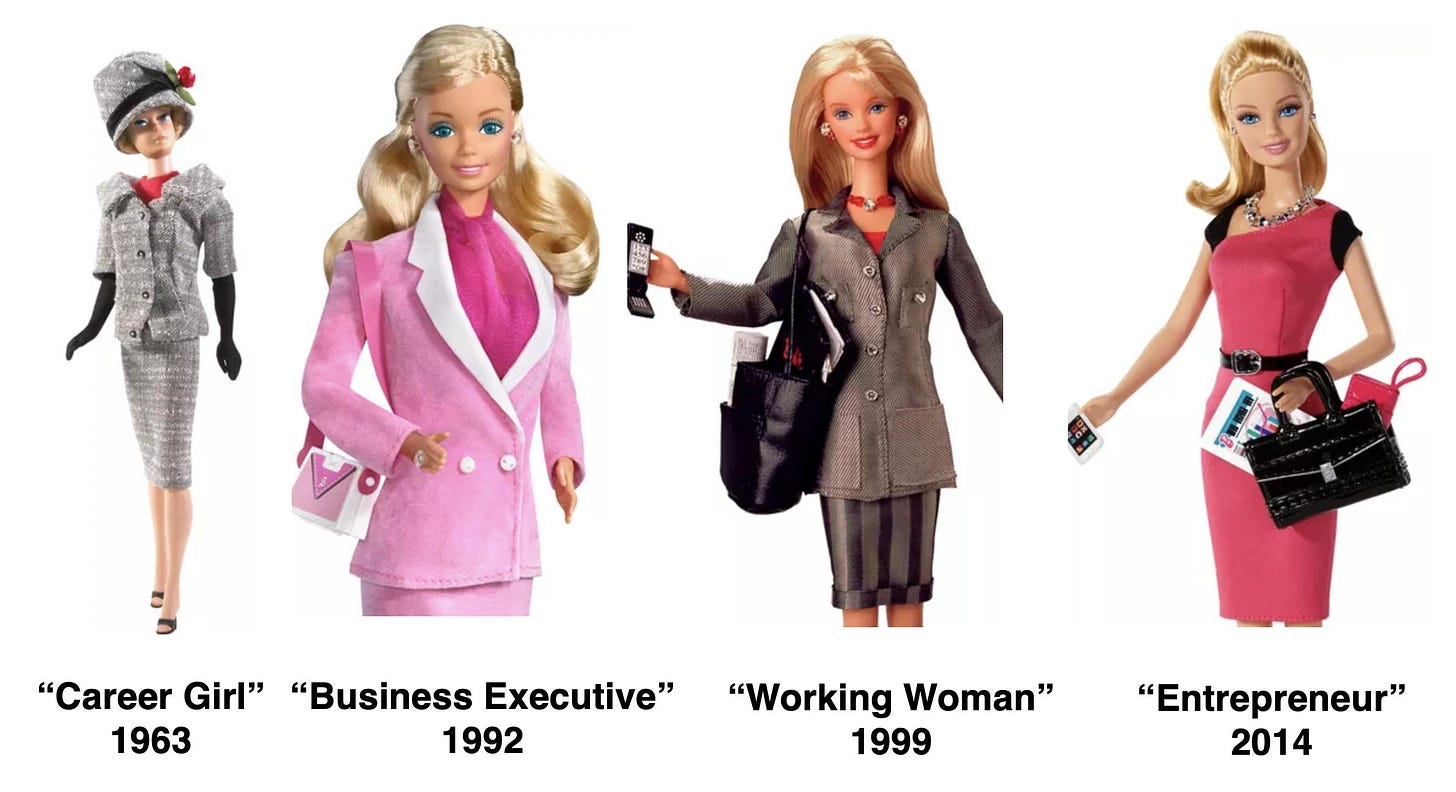

Girl Culture: An Encyclopedia, edited by Claudia A. Mitchell and Jaqueline Reid-Walsh, recounts the history of dolls and Barbie from a third-wave feminist perspective dominant at the time of its 2008 publication. The book describes how Ruth Handler, the designer primarily responsible for the development of the original Barbie, modeled the doll based on her observations of young girls’ play. These girls didn’t want to simply infantilize baby dolls, but to use their imagination to play with aspirational figures whom they could admire. A major part of Barbie’s brand identity since her inception has been her resume; she’s always been a working girl. In fact, a boundary-pushing career-driven Barbie has existed for far longer than some may think; the first astronaut Barbie was released in 1965, almost two decades before Sally Ride would become the first American woman in space (Valentina Tereshkova, a Soviet cosmonaut, achieved the feat two years before Barbie). If anyone can “have it all,” it’s Barbie: she’s gainfully employed, owns a home, has a cute and kind-of-gay boyfriend (every woman’s dream), a dog, and no kids. The original success of Barbie was in her fundamental adult-ness; the cornerstone of her design, her humanity being what separated her from both the baby dolls and fashion dolls she competes with. Barbie has always been a woman first and foremost—or rather, a representation of womanhood.

If Barbie is a prisoner of culture war, pushback has only made her stronger. The feminist backlash against Barbie to be more inclusive, more empowered, more “real,” recognizes and actively creates a cultural truth: Barbie’s job is to teach girls how to be women. The fight for a Better Barbie was born out of genuine concern for girls’ body image and self worth, but it also serves an unintentional purpose as free market research for Mattel. Lisa Simpson’s quest for a better Malibu Stacy begins with a plea to the company itself—she wants them to create a product that will teach girls empowerment. For better or worse, Barbie is an American icon. She was born into the Cold War, she loves to shop, and she lives on the Malibu coast—the last stop on the journey to Manifest Destiny. Teen Talk Barbie met controversy for her line about thinking math class is hard, but perhaps we should have been more concerned about something that seems far more mundane: her predilection for shopping.

It’s true that femininity is seen as inherently weak, that things described as “girly” are subject to unfair derision, and women that take on a more feminine appearance are frequently treated as if they are stupid or vapid. For girls that dream of taking the MCAT in stilettos, Barbie is undoubtedly a source of unapologetically feminine empowerment in a man’s world. But while teaching girls that femininity can be empowering, Barbie simultaneously teaches girls that asserting womanhood comes from consumption. Barbie has always been flawless. She has been a doctor, a pilot, a sergeant in the United States Marine Corps, and a cat burglar. She has been so many things it’s almost impossible to say what Barbie consistently is, but there is perhaps one defining aspect of her being that has remained unchanged since her inception: Barbie is beautiful. Not only do girls learn to want Barbie dolls, they learn to want shopping, makeup, wardrobes full of clothes, not in addition to empowerment but as a fundamental requisite for modern and complete womanhood. Barbie has been many things, but if there’s one thing she’s never been, it’s a minimalist.

The casting of Gerwig’s Barbie film shows that anyone can be a Barbie regardless of size, race, age, sexuality. Barbie is framed as universal, as accessible; after all, a Barbie doll is an inexpensive purchase and Barbiehood is a mindset. Gerwig’s Barbie is a film for adults, not children (as evidenced by its PG-13 rating, Kubrick references, and soundtrack), and yet it manages to achieve the same goals as its source material: developing brand loyalty to Barbie™ and reinforcing consumerism-as-identity as a modern and necessarily empowering phenomenon. Take, for example, “Barbiecore,” an 80s-inspired trend whose aesthetic includes not only hot pink but the idea of shopping itself. This is not Marx’s theory on spending money for enjoyment, nor can it even be critically described as commodity fetishism, because the objects themselves bear less semiotic value compared to the act of consumption and the identity of “consumer.”

Perhaps it seems silly to place so much stock in a fun summer film that hasn’t been released yet, perhaps it seems condescending to insult the critical thinking of adults who want to watch a fun movie. But this Barbie Revisionism as an excuse for consumerism isn’t a future prediction, it’s a present reality—the film has sparked a renewed interest in the Barbie brand for the adult market, the single, no children adult market previously uncaptured by a company that makes children’s toys. Mattel has already planned collaborations with over 100 companies releasing Barbie-branded tie-ins in anticipation of the film, from a luxury candle at Bloomingdales to pink lemonade with sparkling water startup Swoon. Richard Rivas, president of marketing at Farouk Systems, stated in an interview for Modern Retail that “Barbie is iconic when it comes to beauty, but beauty standards are so different now so we developed tools that every consumer can use.” In the same article, Mattel’s chief franchise officer and head of consumer products Josh Silverman notes that,

“As one of the most buzzed-about film releases in recent times, ‘Barbie’ has dominated the zeitgeist for months. This historic moment for Mattel creates incredible fanfare for our partners and consumers alike; we are eagerly looking forward to the film’s release and sharing the multitude of new ways Barbie fans worldwide can celebrate this iconic moment.”

It would be hard to believe that fans of Gerwig’s oeuvre would so easily buy into this cash grab, but to see how effective it’s already been, one simply needs to look into the response to the collaboration between insurance company Progressive and Barbie.

“Lisa vs. Malibu Stacy” is a classic Simpsons episode because it is such a clear embodiment of the function of Lisa Simpson. She is positioned as fundamentally, politically correct. She is also positioned as condescending and just plain old annoying, which undermines her correctness. It is the same criticism faced by the Barbie Liberation Organization and the Barbie dissidents of the twentieth century. Part of the brilliance of the Barbie brand is its emphasis on having fun; critiquing Barbie’s feminism is seen as a dated, 90s position and the critic as deserving of a dated, 90s epithet: feminist killjoy. It’s just a movie! It’s just a toy! Life is so exhausting, can’t we just have fun? I’ve written extensively about how “feeling good” is not an apolitical experience and how the most mundane pop culture deserves the most scrutiny, so I won’t reiterate it here. But it is genuinely concerning to see not only the celebration of objects and consumer goods, but the friendly embrace of corporations themselves and the concept of intellectual property, marketing, and advertising. Are we so culturally starved that insurance commercials are the things that satiate our artistic needs?

When we speak about Barbie, it is shockingly easy to recognize her personhood, to describe “who she is.” It is much harder to talk about Barbie in terms of “what it is”—a combination of plastics available for purchase. It is no coincidence that Barbie’s creation coincided with the post-War shift in disposable consumer goods; Barbie’s wide array of career options and outfits meant that Barbies could be collected, traded, and disposed of—a markedly different attitude towards dolls than the expensive porcelain creations of the early 20th century. Barbie is a woman (or at least, an evocation of one), but Barbie™ is a brand. It is probably one of the first brands that children are aware of, one with a long history of corporate tie-ins… the first inter-brand Barbie was simply called “Barbie Loves McDonalds.” By placing Barbie at the center of debates about girlhood and womanhood, we have allowed the brand to maintain its place at the heart of our culture. And as Barbie becomes more inclusive, more friendly, more aspirational, and more abstract, we must also become sharper, more critical, and more grounded about what Barbie is actually selling us. In short, as we find ourselves seated for Gerwig’s film in our hairspray and hot pink outfits, we must become Lisa Simpsons.

I think they may have had a genuine stroke when they first saw Bratz dolls.

Correct! The diagnosis for this condition is called “internalized misogyny.” Nowadays, I love beautiful women. If you’re looking for a “How I Stopped Worrying And Learned To Love The Mini-Skirt” essay, you’ll have to look elsewhere. It’s a bit too tired a topic for me to care about. Sorry!

So excited for this ironic quasi-critique of consumerism that gets a lot of praise from critics, even though i know it'll just be pure unadulterated product placement.

Those tweets about loving the marketing for this movie make me sad